By Stephanie Nixon, QAS Advanced Care Paramedic II

Charleville, Bidjara Country

'Everyone has multiple and diverse identities that combine in unique ways to shape their perspectives and experiences with oppression/privilege'

Diversity: The mix of people in the organisation

Inclusion: The mix of people working together

Intersectionality: The unique life experience and world views of individuals, taking into account their individual experiences of power and marginalisation

Diversity and inclusion are increasingly popular terms, often heard around workplaces, forums, conferences, and government. But what do they mean in the context of paramedicine and why do they matter for our staff, our organisations, and our patients?

At its core, diversity refers to all the ways we are different. This can include race, gender, sexuality, age, social status, body size, religion, ability, education, or geography. There are many ways that people differ.

Inclusivity is feeling like you belong. When individuals feel respected for who they are as individuals, they feel connected to their co-workers and peers. When they’re given opportunities to develop their careers and progress within the organisation, they feel that they can contribute in a meaningful way. Inclusivity can be challenging for large organisations to achieve, but it is essential.

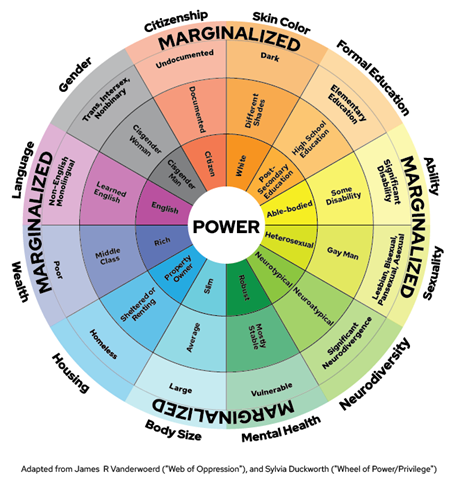

The “intersectionality” image of the wheel of power, privilege and marginalisation varies depending on the country and organisation, but the concept is the same. This model looks at the complex relationship between social identities and systems of power/oppression.

Everyone has multiple and diverse identities that combine in unique ways to shape their perspectives and experiences with oppression/privilege. The closer the trait is to the middle, the more power (privilege) it has; the further it is from the middle, the more marginalised (less privilege) it is. This wheel is a great way to understand where you fall and where others may fall within the oppression/privilege paradigm.

It’s a timely reminder to reflect on where you sit, where others within your organisation - such as peers, managers and students - sit, as well as where patients sit. It’s important to reflect and understand how certain differences can have profound impacts on how a person exists in the world, and how they experience their life.

For example, a slim, white, middle-aged, straight, middle class, male living in Australia will mainly fall within the areas closest to power. However, a non-English speaking, mildly disabled, high-school educated, bisexual male living in Australia will be closer to the marginalised area then to power. This is a way to understand who is at risk of being marginalised and can provide an opportunity for us to reflect on our own areas of privilege while considering areas of marginalisation when we are interacting with our diverse patient cohorts.

The Diversity Council Australia has in the past seven years biannually been tracking diversity and inclusivity within Australian workplaces. Their latest data available shows that non-inclusive teams have increased in the past two years, and concerningly only 31% of workers reported that their manager was inclusive. The same study found 52% of workers reported that their organisation was inclusive, which meant workers felt they were treated fairly, felt diversity was valued and respected, and that their top leaders demonstrated a genuine commitment to diversity and inclusion (Diversity Council Australia, 2024).

Unfortunately, post-pandemic discrimination and harassment have increased. 30% of workers responded yes when asked if they had experienced discrimination and/or harassment at work in the past 12 months. Workers from marginalised backgrounds reported significantly higher levels of discrimination and/or harassment at work compared with workers from non-marginalised backgrounds. Of the 30% who said yes, 59% identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander workers, 42% were workers with disability, 40% were workers with a non-Christian religion, and 39% were LGBTIQ+ workers (Diversity Council Australia, 2024). When we look back at the wheel, we start to understand the other marginalised groups that are at higher risk of experiencing discrimination and/or harassment.

If workers are being discriminated and/or harassed within the workplace we don’t have an inclusive workplace, no matter how diverse the employees may be. Studies have shown that workplaces with inclusive and representative workforces benefit greatly from this inclusivity. They report higher workplace retention, workers are less likely to experience discrimination and/or harassment, workers experience increased wellbeing, there are increased opportunities at work, improved access to care for patients, higher patient satisfaction, and improved patient-centred care (Smedley et al, 2004; Brown et al, 2018; Diversity Council Australia, 2024; Wallis et al, 2022).

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) Code of Conduct Section Three refers to the provision of respectful and culturally safe practices. This part of the code explains how practitioners should have knowledge of how their own culture, values, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs influence their interactions with others (Ahpra, 2022). In simple terms, using the above image as a tool, a practitioner can reflect and understand where they sit on the wheel of power, while also considering where their patients might be sitting on the same wheel. By so doing, the practitioner can support a safe and inclusive environment for others.

Inclusivity has proven positive effects. In inclusive work cultures, LGBTIQ+ people were three times more likely as workers in non-inclusive cultures to be “out” to their colleagues, a unique experience that many felt was important to them (Brown et al., 2018). Workers in inclusive workplaces were 9.5 times more likely to be innovative than non-inclusive teams, were 8.5 times more likely to work effectively together and four times more likely to provide excellent customer care (Diversity Council Australia, 2024). Further evidence strongly suggests that group collaboration is greatly improved by the presence of women in the group (Woolley et al. 2010).

In the broad workplace of paramedicine, the impact of inclusive workplaces is limitless. It impacts us, our colleagues, and our patients. Inclusivity in progressive management spaces ensures policies reflect the need of the workforce and the communities we serve. Would maternity care guidelines be done without consulting a midwife/obstetrician? Would trauma care guidelines be done without consulting doctors, surgeons, specialists? Would cardiac arrests guidelines be completed without input from the Australian Resuscitation guidelines? I doubt it. So we shouldn’t make policies without consulting the people they impact. Similarly, we need to have the representation in our workforce that reflects our communities so we can ensure we are being inclusive of the needs of those we serve. As the saying goes, “if you want to go faster, go alone; if you want to go further, go together”.

References

Ahpra. (2022). Shared code of conduct. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Code-of-conduct/Shared-Code-of-conduct.aspx

Brown, C, O'Leary, J, Trau, R, Legg, A, (2018). Out at Work: From Prejudice to Pride. Retrieved from Sydney, NSW: https://www.dca.org.au/research/lgbtiq-out-at-work

Diversity Council Australia (D’Almada-Remedios, R.), DCA Inclusion@Work Index 2023-2024: Mapping the State of Inclusion in the Australian Workforce, Sydney, Diversity Council Australia, 2024

Marjadi, B, Flavel, J, Baker, K, et al., (2023). Twelve Tips for Inclusive Practice in Healthcare Settings. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(5), 4657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054657

Mullaly, Bob, Challenging oppression and confronting privilege: A critical social work approach. Oxford University Press, 2010

Smedley, B.D, Butler, A.S, Bristow, L.R, (2004). Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the US Health Care Workforce, Institute of Medicine (US), Board on Health Sciences Policy. In the nation’s compelling interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce.

Wallis, C.J, Jerath, A, Coburn, N, Klaassen, Z. et al., (2022). Association of surgeon-patient sex concordance with postoperative outcomes. JAMA surgery, 157(2), 146-156.

Woolley, A, Chabris, C, et al., (2010). Evidence of a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups. Science (New York, NY). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47369848_Evidence_of_a_Collective_Intelligence_Factor_in_the_Performance_of_Human_Groups

Get unlimited access to hundreds of ACP's top courses for your professional development.

Join Now