By Mark Garner

Mark worked as an Offshore Critical Care and Extended Care Paramedic in both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, and was an undergraduate lecturer teaching paramedicine. He now works as a consultant to the industry.

'As the role of paramedics continues to diversify, it is important that they become more integrated into the emergency management teams.'

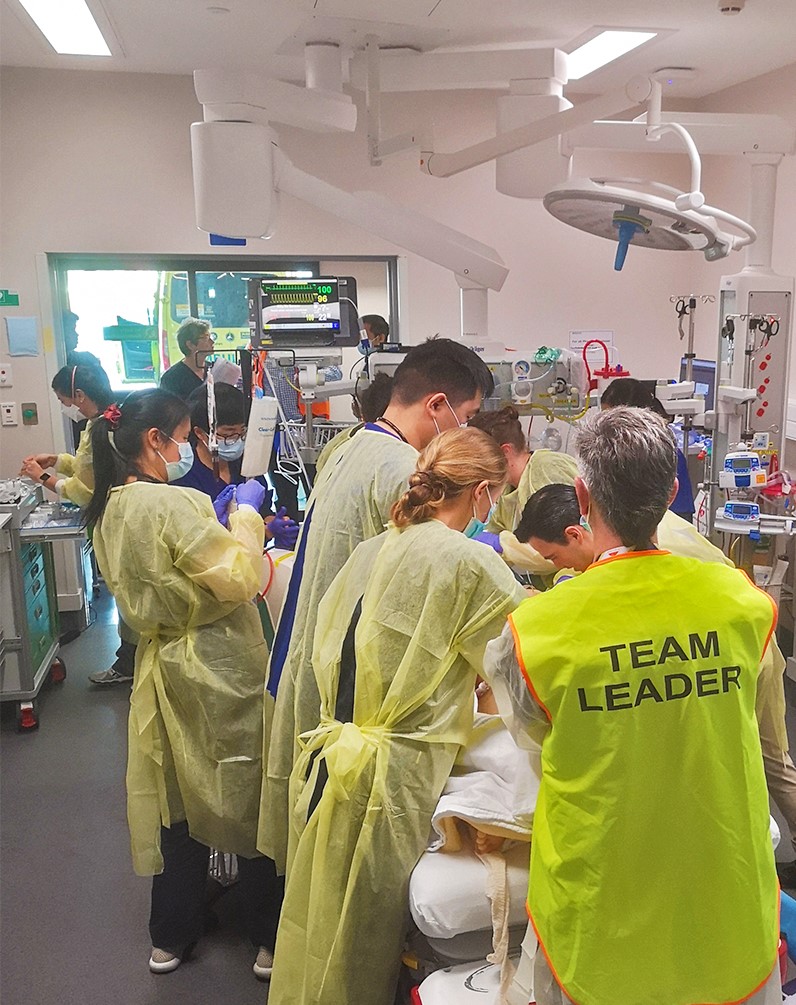

As a retired Critical Care and Extended Care/Remote Paramedic, I was recently invited to be an observer on a NetworkZ trauma simulation training scenario, held in a major hospital emergency department in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The simulation package run by NetworkZ, a division of the University of Auckland’s Uniservices department, was developed more than eight years ago by a team of clinicians and academics using a high-fidelity manikin and realistic special effects overlays to allow interdisciplinary teams to practise their skills with convincingly authentic scenarios. It is backed by robust academic research and rolled out throughout the country in multiple care settings.

The manikin talks, blinks, bleeds, breathes, has pulses, can be intubated and cannulated, and have chest drains inserted, as well as feature realistic wounds, amputations, or various other injuries. It is as realistic as one can get without using a real patient. It is remotely controlled by a technician who can alter any parameter, including heart rate, cardiac rhythm, SpO2, etCO2, respirations, pupils, eyes, and pretty much everything else except movement and colour.

Facilitators of the program brief the teams beforehand, demonstrating how the manikin works and the rules of engagement for the event. Once briefed, the action begins. Of note, all the participants are actual healthcare workers in the roles they would normally perform; doctors, nurses, laboratory involvement, HCAs, and pre-hospital care staff. And all the scenarios are performed in the actual clinical space - in situ.

Just like a realistic event, the scenario begins with an R-40 (radio call to hospital) from the incoming ambulance, informing them of the patient, their injuries, treatment given, status and ETA. The team uses this information, alongside their protocols, to prepare for the imminent arrival and request the attendance of any other team members they think they might need.

After roughly five minutes, the “patient” is wheeled in the door and the paramedic gives their typical handover, introducing the patient, highlighting their injuries, treatment, and any other relevant information. After assisting with transferring the patient on to the ED stretcher, they exit the room or can stay and assist if requested. In my case, I stood back and observed.

This is what I learnt from the experience:

The R-40 information is critically important

While it is routine for paramedics to call in an R-40 for status one or two patients, I underestimated the importance of the information we give. The mechanism of injury and baselines of the patient can be used to determine what experts are called into the resuscitation room. I also realised one of the things we don’t mention in R-40s that would be helpful to ED is an estimated weight of the patient. We use this information in the field to guide the drug doses we give, and passing this vital piece of information in an R-40 can also help them to prepare and draw up drug dosages before the ambulance arrival. Timing of the R-40 is also important. Giving it around 15-20 minutes seems to be the optimal time so the right resources can be summoned without them waiting around too long for the ambulance arrival.

Our contribution doesn’t have to stop after handover

Traditionally, ambulance staff deliver and hand over the patient to the hospital ED staff and then walk away to do a clean-up and complete the paperwork. There is, however, an appetite from some hospital staff that they actually stay and continue clinical involvement in the patients' treatment in the resuscitation room. In the debrief I witnessed, it was discussed what happens if the unit is short-staffed, critically busy, or there is simply not the staff available to carry out the many tasks that need doing. One of the senior doctors said she would love it if the paramedics stayed and helped if they could. She recognised the diverse skill set paramedics have and said their skills could often be well utilised during resuscitation efforts. It also became evident that sticking around meant that paramedics were able to answer further questions about the patient that the hospital staff may have as the resuscitation efforts progressed.

Bleeding control

Paramedics often do their best to pack and bandage up severe wounds to mitigate bleeding, but if the dressings are soaked in blood then they will likely be quickly torn off by the surgeon in an effort to stop bleeding. The surgeon in this scenario said if it appeared that bleeding had not been stopped, even with a tourniquet in situ, that he would often attempt to physically identify the offending blood vessel(s) and clamp them directly, even if it meant simply squeezing it with his fingers. He said it was far more effective than just tightening a torniquet.

A picture is worth a thousand words

A photo, or photos taken from the scene (with the patients' permission where possible, of course), can provide additional valuable information that may otherwise be overlooked. As a paramedic, I made it a routine habit to take quick scene shots with the ePRF tablet to show ED staff what the incident looked like, what was the environment looked like, how the patient was encased/trapped, or what their injuries or wounds looked like at the scene prior to splinting/dressing. ED staff always appreciated the extra information the photos presented. In the scenario I watched, I realised that if a photo of the scene had been included, it may have enhanced the handover information given. I think we often underestimate the value such pictures can bring, and this would also be an area worthy of some academic research.

The information in the ePRF follows the patient through their hospital journey

The information entered into the ambulance ePRF, including your description of the event, treatment and baselines, ECGs and photos, is often used by specialists throughout the hospital during the patients' journey through the hospital system. It may be used as a basis for important clinical decisions or, in the event the patient dies, by the coroner, so it is vital to make sure it is as accurate and descriptive as it can be! Use the timelines provided in the monitor summary to ensure times of actions are entered as accurately as possible.

While paramedics carry out multiple roles to treat the patient, this is done by specialist teams in hospital

Hospitals work in specialist teams. This includes an airway team (anaesthetists, anaesthetic technicians, and airway nurses) who take care of the airway and breathing, a surgical team (typically a surgical registrar who looks at the fractures, circulation, organ damage and blood loss), pharmacy (medication nurses and pharmacists who draw up the drugs), ED doctors (registrars, senior medical officers, and house officers who generally run the resuscitation), a scribe (to take down notes and/or write them up on the whiteboard), orderlies and healthcare assistants (who often fetch equipment or may do CPR) and an IV nurse (cannulating and setting up fluids). Depending on the hospital, you may also have someone from plastics, neurology, obstetrics, orthopaedics, radiology, blood bank and intensive care. This is why the resus room can suddenly become so crowded.

Interdisciplinary interaction can be complex and practise helps perfect it

The huge advantage of this interdisciplinary training is that it helps to ensure that these expert teams work effectively, efficiently, and that ultimately the patient benefits from the treatments being given - and in a timely fashion. It also can identify latent threats that will only show up when such simulations are carried out and when training is done in the actual clinical workspace. Is the equipment fit for purpose and in the right place? Are there sufficient quantities of the right medications? Are there barriers (physical or otherwise) to effective communication? Is the layout of the room effective?

Don’t forget the whanau (family)

As paramedics, we use the pneumonic IMISTAMBO when giving a handover to ensure we pass on the most important and relevant information. One thing that could be added to the end of this is W (for whanau) or F (for family). Letting the ED staff know what family members, if any, have accompanied the patient or are in the waiting room is important information both for those family members and the patient so they can be kept informed of the patient’s care.

As the role of paramedics continues to diversify, it is important that they become more integrated into the emergency management teams, and the NetworkZ simulation training is an excellent way to do this in a non-threatening, safe, equitable environment. If you are offered the chance to participate in a NetworkZ training, I would highly recommend it. Not only will it count towards your CPD hours, but it will help to improve communication, relationships, and appreciation of the paramedic’s role in the overall healthcare system.

Get unlimited access to hundreds of ACP's top courses for your professional development.

Join Now